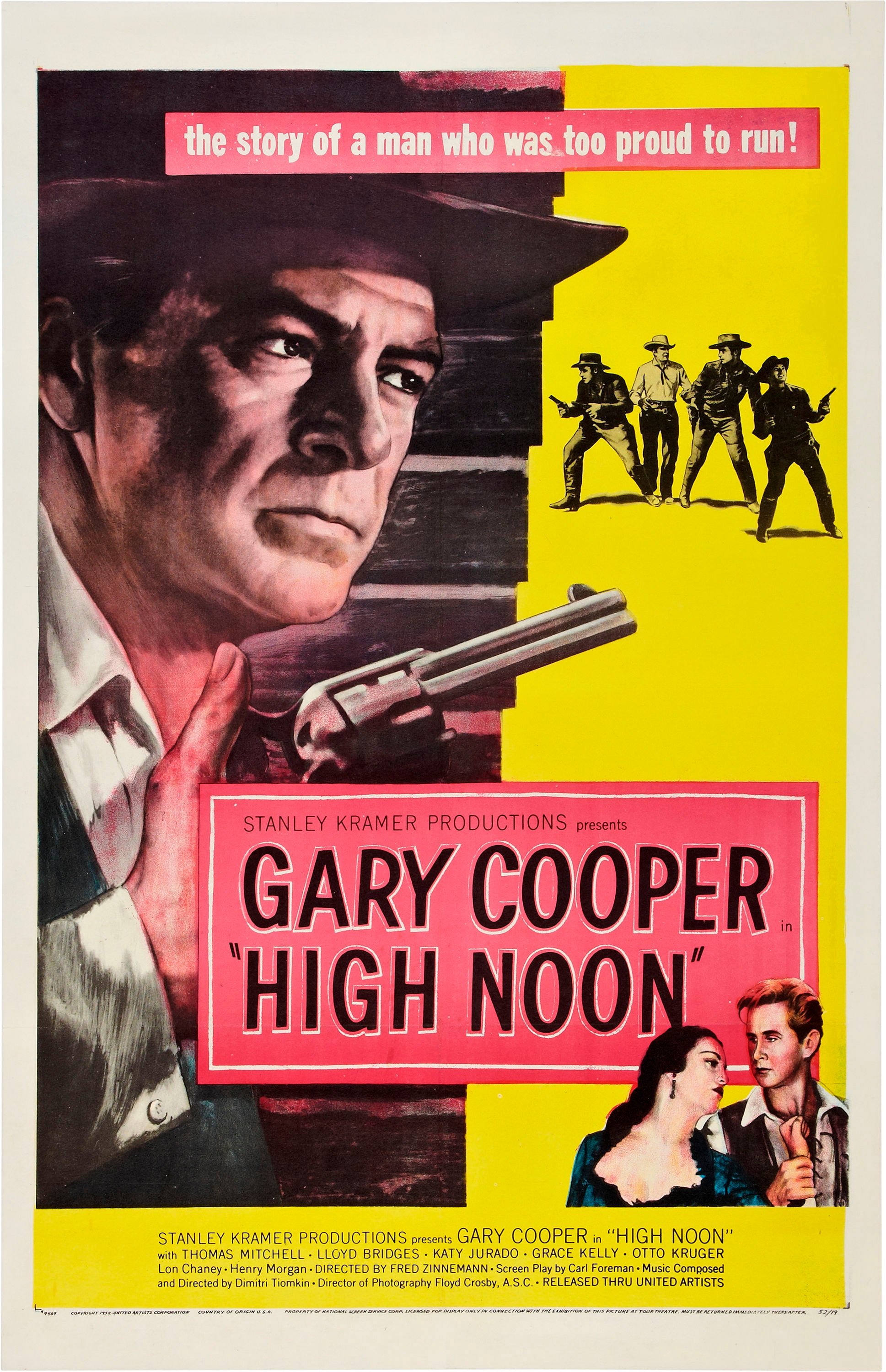

High Noon (Film)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| High Noon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Fred Zinnemann |

| Screenplay by | Carl Foreman |

| Based on | “The Tin Star” 1947 short story in Collier’s by John W. Cunningham |

| Produced by | Stanley Kramer (uncredited) |

| Starring | Gary Cooper Thomas Mitchell Lloyd Bridges Katy Jurado Grace Kelly Otto Kruger Lon Chaney Henry Morgan |

| Cinematography | Floyd Crosby |

| Edited by | Elmo Williams Harry W. Gerstad |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

| Production company | Stanley Kramer Productions |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

| Release date | July 24, 1952 |

| Running time | 85 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $730,000 |

| Box office | $12 million |

High Noon is a 1952 American Western film produced by Stanley Kramer from a screenplay by Carl Foreman, directed by Fred Zinnemann, and starring Gary Cooper. The plot, which occurs in real time, centers on a town marshal whose sense of duty is tested when he must decide to either face a gang of killers alone, or leave town with his new wife.

Though mired in controversy at the time of its release due to its political themes, the film was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four (Actor, Editing, Score and Song) as well as four Golden Globe Awards (Actor, Supporting Actress, Score, and Black and White Cinematography). The award-winning score was written by Ukraine-born composer Dimitri Tiomkin.

High Noon was selected by the Library of Congress as one of the first 25 films for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” in 1989. An iconic film whose story has been partly or completely repeated in later film productions, its ending in particular has inspired numerous later films, including but not just limited to westerns.

Plot

In Hadleyville, a small town in New Mexico Territory, Marshal Will Kane, newly married to Amy Fowler, prepares to retire. The happy couple will soon depart to raise a family and run a store in another town. However, word arrives that Frank Miller, a vicious outlaw whom Kane sent to prison, has been released and will arrive by the noon train, one day ahead of the new marshal. Miller’s gang—his younger brother Ben, Jack Colby, and Jim Pierce—wait at the station.

For Amy, a devout Quaker and pacifist, the solution is simple—leave town before Miller arrives—but Kane’s sense of duty and honor make him stay. Besides, he says, Miller and his gang would hunt him down anyway. Amy gives Kane an ultimatum: she is leaving on the noon train, with or without him.

Kane visits old friends and allies, but none can or will help. Judge Percy Mettrick, who sentenced Miller, flees and urges Kane to do the same. Harvey Pell, Kane’s young deputy, is bitter that Kane did not recommend him as his successor; he says he will stand with Kane only if Kane “puts the word in” for him with the city fathers. When Kane refuses, Pell turns in his badge and pistol. Kane’s efforts to round up a posse at Ramírez’s Saloon and the church are met with fear and hostility. Some townspeople, worried that a gunfight would damage the town’s reputation, urge Kane to avoid the confrontation. Some are Miller’s friends, but others resent that Kane cleaned up the town in the first place. Others believe that Kane’s fight is not the town’s responsibility. Sam Fuller hides in his house, forcing his wife Mildred to tell Kane he is not home. Jimmy offers to help, but he is blind in one eye, sweating, and unsteady. The mayor encourages Kane to leave town. Martin Howe, Kane’s predecessor, is too old and arthritic. Herb Baker agrees to be deputized, but backs out when he realizes he is the only volunteer. One last offer of help comes from 14-year-old Johnny. Kane admires his courage, but refuses his aid.

While waiting at the hotel for the train, Amy confronts Helen Ramírez, who was once Miller’s lover, then Kane’s, then Pell’s. Amy believes the reason Kane refuses to leave town is because he wants to protect Helen, but Helen reveals there is no lingering attachment on Kane’s part and she, too, is leaving. When Helen questions why Amy will not stay with Kane, Amy explains that both her brother and father were gunned down by criminals, a tragedy that converted her to Quakerism. Helen nonetheless chides Amy for not standing by her husband in his hour of need, saying that if she was in Amy’s place, she would take up a gun and fight alongside Kane.

Pell saddles a horse and tries to persuade Kane to take it. They end up in a fist fight. After knocking Pell senseless, Kane returns to his office to write out his will. As the clock ticks toward noon, Kane goes into the street to face Miller and his gang. Amy and Helen ride by on a wagon, bound for the train. The train arrives, and Miller steps off as the two ladies board.

Kane walks down the deserted main street alone. He manages to kill Frank Miller’s brother, Ben, in the opening salvo. Just before the train departs, Amy hears the gunfire and runs back to town. Kane takes refuge in a stable, and Colby is killed when he comes in after him. Miller sets fire to the stable to flush him out. Kane frees the horses and tries to escape on one, only to be shot off and cornered. Despite her religious beliefs, Amy picks up Pell’s pistol and shoots Pierce from behind, leaving only Frank Miller, who grabs Amy as a human shield to force Kane into the open. When Amy claws Miller’s face, he pushes her to the ground and Kane shoots him dead.

The couple embrace. As the townspeople emerge, Kane smiles at Johnny, but looks angrily at the rest of the crowd. He drops his marshal’s star to the street and departs with Amy.

Cast

Main cast

- Gary Cooper as Marshal Will Kane

- Thomas Mitchell as Mayor Jonas Henderson

- Lloyd Bridges as Deputy Marshal Harvey Pell

- Katy Jurado as Helen Ramírez

- Grace Kelly as Amy Fowler Kane

- Otto Kruger as Judge Percy Mettrick

- Lon Chaney Jr. as Martin Howe, the former marshal

- Harry Morgan as Sam Fuller

- Ian MacDonald as Frank Miller

- Eve McVeagh as Mildred Fuller

- Morgan Farley as Dr. Mahin, minister

- Harry Shannon as Cooper

- Lee Van Cleef as Jack Colby

- Robert J. Wilke as Jim Pierce

- Sheb Wooley as Ben Miller

Uncredited

- James Millican as Herb Baker

- Howland Chamberlain as the hotel desk clerk

- Tom London as Sam, Helen’s attendant

- Cliff Clark as Ed Weaver, Helen’s saloon tenant

- William Newell as Jimmy the Gimp

- Larry J. Blake as Gillis the saloon owner

- Lucien Prival as Joe the Bartender

- Jack Elam as Charlie, the town drunk

- John Doucette as Trumbull

- Tom Greenway as Ezra

- Dick Elliott as Kibbee

- Merrill McCormick as Fletcher

- Virginia Christine as Mrs. Simpson

- Harry Harvey as Coy

- Paul Dubov as Scott

Production

According to Darkness at High Noon: The Carl Foreman Documents—a 2002 documentary based in part on a lengthy 1952 letter from screenwriter Carl Foreman to film critic Bosley Crowther—Foreman’s role in the creation and production of High Noon has been unfairly downplayed over the years in favor of producer Stanley Kramer’s. Foreman told Crowther that the film originated from a four-page plot outline he wrote that turned out to be very similar to a short story by John W. Cunningham entitled “The Tin Star”.

Foreman purchased the film rights to Cunningham’s story and wrote the screenplay. By the time the documentary aired, most of the principals were dead, including Kramer, Foreman, Zinnemann, and Cooper. Victor Navasky, author of Naming Names, an authoritative account of the Hollywood blacklist, told a reporter that, based on his interviews with Kramer’s widow and others, the documentary seemed “one-sided, and the problem is it makes a villain out of Stanley Kramer, when it was more complicated than that”.

Years later, director Richard Fleischer claimed that he helped Foreman develop the story of High Noon over the course of eight weeks while driving to and from the set of the 1949 film The Clay Pigeon, which they were making together. Fleischer said that his RKO contract prevented him from directing High Noon.

There is a description of an incident very similar to the central plotline of High Noon in Chapter XXXV of The Virginian, by Owen Wister, in which Trampas (a villain) calls out The Virginian, who has a new bride waiting whom he might lose if he engages in a gunfight. High Noon has even been described as a “straight remake” of the 1929 film version of The Virginian, which also featured Gary Cooper in a starring role.

House Un-American Activities Committee controversy

The production and release of High Noon intersected with the Second Red Scare in the United States and the Korean War. In 1951, during production of the film, screenwriter Carl Foreman was summoned before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) during its investigation of “Communist propaganda and influence” in the motion picture industry. Foreman had once been a member of the Communist Party, but he declined to identify fellow members or anyone he suspected of current membership. As a result, he was labeled an “uncooperative witness” by the committee, making him vulnerable to blacklisting by the movie industry.

After his refusal to name names was made public, Foreman’s production partner Stanley Kramer demanded an immediate dissolution of their partnership. As a signatory to the production loan, Foreman remained with the High Noon project, but before the film’s release, he sold his partnership share to Kramer and moved to Britain, knowing that he would not find further work in the United States.

Kramer later asserted that he had ended their partnership because Foreman had threatened to falsely name him to HUAC as a Communist. Foreman said that Kramer feared damage to his own career due to “guilt by association”. Foreman was indeed blacklisted by the Hollywood studios due to the “uncooperative witness” label along with pressure from Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn, MPA president John Wayne, and Los Angeles Times gossip columnist Hedda Hopper.

Casting

John Wayne was originally offered the lead role in the film, but refused it because he believed that Foreman’s story was an obvious allegory against blacklisting, which he actively supported. Later, he told an interviewer that he would “never regret having helped run Foreman out of the country”. Gary Cooper was Wayne’s longtime friend and shared his conservative political views; Cooper had been a “friendly witness” before HUAC but did not implicate anyone as a suspected Communist, and he later became a vigorous opponent of blacklisting. Cooper won an Academy Award for his performance, and since he was working in Europe at the time, he asked Wayne to accept the Oscar on his behalf. Although Wayne’s contempt for the film and refusal of its lead role were well known, he said, “I’m glad to see they’re giving this to a man who is not only most deserving, but has conducted himself throughout the years in our business in a manner that we can all be proud of … Now that I’m through being such a good sport … I’m going back to find my business manager and agent … and find out why I didn’t get High Noon instead of Cooper …”

After Wayne refused the Will Kane role, Kramer offered it to Gregory Peck, who declined because he felt it was too similar to his role in The Gunfighter, the year before. Peck later said he considered it the biggest mistake of his career. Marlon Brando, Montgomery Clift, and Charlton Heston also declined the role.

Kramer saw Grace Kelly in an off-Broadway play and cast her as Kane’s bride, despite Cooper and Kelly’s substantial age disparity (50 and 21, respectively). Rumors of an affair between Cooper and Kelly during filming remain unsubstantiated. Kelly biographer Donald Spoto wrote that there was no evidence of a romance, aside from tabloid gossip. Biographer Gina McKinnon speculated that “there might well have been a roll or two in the hay bales”, but cited no evidence, other than a remark by Kelly’s sister Lizanne that Kelly was “infatuated” with Cooper.

Lee Van Cleef made his film debut in High Noon. Kramer first offered Van Cleef the Harvey Pell role, after seeing him in a touring production of Mister Roberts, on the condition that Van Cleef have his nose surgically altered to appear less menacing. Van Cleef refused and was cast instead as Colby, the only role of his career without a single line of dialog.

Filming

High Noon was filmed in the late summer/early fall of 1951 in several locations in California. The opening scenes, under the credits, were shot at Iverson Movie Ranch near Los Angeles. A few town scenes were shot in Columbia State Historic Park, a preserved Gold Rush mining town near Sonora, but most of the street scenes were filmed on the Columbia Movie Ranch in Burbank.

St. Joseph’s Church in Tuolumne City was used for exterior shots of the Hadleyville church. The railroad was the old Sierra Railroad in Jamestown, a few miles south of Columbia, now known as Railtown 1897 State Historic Park, and often nicknamed “the movie railroad” due to its frequent use in films and television shows. The railroad station was built for the film alongside a water tower at Warnerville, about 15 miles to the southwest.

Cooper was reluctant to film the fight scene with Bridges due to ongoing problems with his back, but eventually did so without the use of a stunt double. He wore no makeup to emphasize his character’s anguish and fear, which was probably intensified by pain from recent surgery to remove a bleeding ulcer.

The running time of the story almost precisely parallels the running time of the film—an effect heightened by frequent shots of clocks to remind the characters (and the audience) that the villain will be arriving on the noon train.

Music

The movie’s theme song, “High Noon” (as it is credited in the film), also known by its opening lyric, “Do Not Forsake Me, Oh My Darling”, became a major hit on the country-and-western charts for Tex Ritter, and later, a pop hit for Frankie Laine as well.

Its popularity set a precedent for theme songs that were featured in many subsequent Western films. Composer Dimitri Tiomkin‘s score and song, with lyrics by Ned Washington, became popular for years afterwards and Tiomkin became in demand for future westerns in the 1950s like Gunfight at the O.K. Corral and Last Train from Gun Hill.

High Noon Covers

- Connie Francis

- Instrumental By Dave Monk

- Duane Eddy

- The Shadows

- Mantovani and His Orchestra

- Billy Vaughn

- Geoff Love & His Orchestra

Reception

The film earned $3.75 million in theatrical rentals at the North American box office in 1952.

Upon its release, critics and audiences expecting chases, fights, spectacular scenery, and other common Western film elements were dismayed to find them largely replaced by emotional and moralistic dialogue until the climactic final scenes. Some critics scoffed at the unorthodox rescue of the hero by the heroine. David Bishop argued that had Quaker Amy not helped her husband by shooting a man in the back, such inaction would have pulled pacifism “toward apollonian decadence”. Alfred Hitchcock thought Kelly’s performance was “rather mousy” and lacking in animation; only in later films, he said, did she show her true star quality.

High Noon has been cited as a favorite by several U.S. presidents. Dwight Eisenhower screened the film at the White House, and Bill Clinton hosted a record 17 White House screenings of it. “It’s no accident that politicians see themselves as Gary Cooper in High Noon,” Clinton said. “Not just politicians, but anyone who’s forced to go against the popular will. Any time you’re alone and you feel you’re not getting the support you need, Cooper’s Will Kane becomes the perfect metaphor.” Ronald Reagan cited High Noon as his favorite film, due to the protagonist’s strong commitment to duty and the law.

By contrast, John Wayne told an interviewer that he considered High Noon “the most un-American thing I’ve ever seen in my whole life,” and later teamed with director Howard Hawks to make Rio Bravo in response. “I made Rio Bravo because I didn’t like High Noon,” Hawks explained. “Neither did Duke [Wayne]. I didn’t think a good town marshal was going to run around town like a chicken with his head cut off asking everyone to help. And who saves him? His Quaker wife. That isn’t my idea of a good Western.”

Zinnemann responded, “I admire Hawks very much. I only wish he’d leave my films alone!” In a 1973 interview, Zinnemann added, “I’m rather surprised at Hawks’ and Wayne’s thinking. Sheriffs are people and no two people are alike. The story of High Noon takes place in the Old West but it is really a story about a man’s conflict of conscience. In this sense it is a cousin to A Man for All Seasons. In any event, respect for the Western hero has not been diminished by High Noon.”

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 95% of 91 critics’ reviews are positive, with an average rating of 8.8/10. The website’s consensus reads: “A classic of the Western genre that broke with many of the traditions at the time, High Noon endures — in no small part thanks to Gary Cooper’s defiant, Oscar-winning performance.” Metacritic, which uses a weighted average, assigned the film a score of 89 out of 100, based on 7 critics, indicating “universal acclaim”.

The film was criticized in the Soviet Union as “glorification of the individual”.

Accolades

Entertainment Weekly ranked Will Kane on their list of The 20 All Time Coolest Heroes in Pop Culture.

American Film Institute recognition

- 1998 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies #33

- 2001 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Thrills #20

- 2003 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Heroes and Villains:

- Will Kane, Hero #5

- 2004 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Songs:

- 2005 AFI’s 100 Years of Film Scores #10

- 2006 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Cheers #27

- 2007 AFI’s 100 Years … 100 Movies (10th Anniversary Edition) #27

- 2008 AFI’s 10 Top 10 #2 Western film

Legacy and cultural influence

High Noon is considered an early example of the revisionist Western. Kim Newman calls it the “most influential Western of the 1950s (because) its attitudes subtly changed the societal vision of the whole (Western) genre”. The traditional format of the Western is of a strong male character leading the civilized against the uncivilized but in this film, the civilized people fail (in a way described by John Wayne as “un-American”) to support their town marshal. Newman draws the contrast between the “eerily neat and civilised” town of Hadleyville and the “gutlessness, self-interest and lack of backbone exhibited by its inhabitants” who will allow the town to “slip back into the savage past” from which Kane and his deputies once saved it.

In his article, The Women of “High Noon”: A Revisionist View, Don Graham argues that in addition to the man-alone theme, High Noon “represents a notable advance in the portrayal of women in Westerns”. Compared with the “hackneyed presentation” of stereotypical women characters in earlier Westerns, High Noon grants the characters of Amy and Helen an expanded presence, the two being counterpoints. While Helen is socially inferior, she holds considerable economic power in the community. Helen’s encounter with Amy is key because she tells Amy that she would never leave Kane if he were her man – she would get a gun and fight, thus predicting Amy’s actions. For most of the film, Amy is the “Eastern-virgin archetype” but her reaction to the first gunshot “transcends the limitations of her genre role” as she returns to town and kills Pierce.

The gang’s actions indicate the implicit but very real threat they pose to women, as is suggested by the Mexican woman crossing herself when the first three ride into town. Graham summarizes the many references to women as a community demoralized by the failure of its male members, other than Kane. The women, he asserts, equal Kane in strength of character to the extent that they are “protofeminists”.

In 1989, 22-year-old Polish graphic designer Tomasz Sarnecki transformed Marian Stachurski’s 1959 Polish variant of the High Noon poster into a Solidarity election poster for the first partially free elections in communist Poland. The poster, which was displayed all over Poland, shows Cooper armed with a folded ballot saying “Wybory” (i.e., elections) in his right hand while the Solidarity logo is pinned to his vest above the sheriff’s badge. The message at the bottom of the poster reads: “W samo południe: 4 czerwca 1989”, which translates to “High Noon: 4 June 1989.”

As former Solidarity leader Lech Wałęsa wrote, in 2004,

Under the headline “At High Noon” runs the red Solidarity banner and the date—June 4, 1989—of the poll. It was a simple but effective gimmick that, at the time, was misunderstood by the Communists. They, in fact, tried to ridicule the freedom movement in Poland as an invention of the “Wild” West, especially the U.S. But the poster had the opposite impact: Cowboys in Western clothes had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom, both physical and spiritual. Solidarity trounced the Communists in that election, paving the way for a democratic government in Poland. It is always so touching when people bring this poster up to me to autograph it. They have cherished it for so many years and it has become the emblem of the battle that we all fought together.

The 1981 science fiction film Outland, starring Sean Connery as a federal agent on an interplanetary mining outpost, has been compared to High Noon due to similarities in themes and plot.

High Noon is referenced several times on the HBO drama series The Sopranos. Tony Soprano cites Gary Cooper’s character as the archetype of what a man should be, mentally tough and stoic. He frequently laments, “Whatever happened to Gary Cooper?” and refers to Will Kane as the “strong, silent type”. The iconic ending to the film is shown on a television during an extended dream sequence in the fifth-season episode “The Test Dream“.

High Noon inspired the 2008 hip-hop song of the same name by rap artist Kinetics, in which High Noon is mentioned along with several other classic Western films, drawing comparisons between rap battles and Western-film street showdowns.

Sequels and remakes

- A television sequel, High Noon, Part II: The Return of Will Kane, was produced in 1980, and aired on CBS in November of that year. Lee Majors and Katherine Cannon played the Cooper and Kelly roles. Elmore Leonard wrote the original screenplay.

- Outland is a 1981 British science fiction thriller film written and directed by Peter Hyams and starring Sean Connery, Peter Boyle, and Frances Sternhagen that was inspired by High Noon.

- In 2000, Stanley Kramer’s widow Karen Sharpe Kramer produced a remake of High Noon as a TV movie for the cable channel TBS. The film starred Tom Skerritt as Will Kane, with Michael Madsen as Frank Miller.

- In 2016, Karen Kramer signed an agreement with Relativity Studios for a feature film remake of High Noon, a modernized version set in the present day at the US-Mexico border. That deal collapsed when Relativity declared bankruptcy the following year, but in 2018, Kramer announced that Classical Entertainment had purchased the rights to the project, which will be produced by Thomas Olaimey with writer-director David L. Hunt. As of 2024, there have been no further developments on it.

Watch The Movie

Part 1

Part 2

Comments